Curated by Najlaa El-Ageli, the ‘Retracing A Disappearing Landscape’ is an interdisciplinary exhibition that is currently on show at the P21 Gallery in London until 12 May. Presenting visual artworks, commissioned installations, films and recent as well as archival photography, it creatively explores people’s direct experience of and fascination with memory and personal history, and approaching the collective narratives that arise in connection to modern day Libya.

The first of its kind internationally, it is also hosting a parallel programme of talks that adds more depth and insight into the themes that come up in the viewing of the artworks and interaction with the installations. Involving over 25 contemporary artists and professionals, both Libyan and non-Libyan, their backgrounds draw upon diverse disciplines that include: poetry, literature, history, research, photojournalism and documentary filmmaking.

Participating artists and professionals are: Najat Abeed, Mohamed Abumeis, Huda Abuzeid, Mohamed Al Kharrubi, Takwa Barnosa, Mohamed Ben Khalifa, Najwa Benshatwan, Alla Budabbus, Malak Elghwel, Elham Ferjani, Yousef Fetis, Hadia Gana, Ghazi Gheblawi, Reem Gibriel, Jihan Kikhia, Marcella Mameli-Badi, Guy Martin, Arwa Massaoudi, Khaled Mattawa, Tawfik Naas, Laila Sharif, Najla Shawket Fitouri, Barbara Spadaro and Adam Styp-Rekowski.

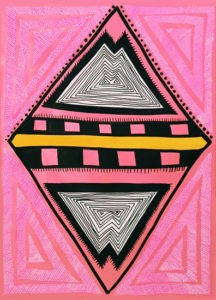

Beginning with the archetypical memories associated with the traditional Libyan family album, the visual elements show images and scenes from private archives that go as far back as the early 1900s. These photos hint at the social fabric of many decades past that has now undergone much felt and visible change. Whilst the second segment features a number of installations that are meant to be temporary repositories and eye-witnesses to the country’s history in different interpretive ways.

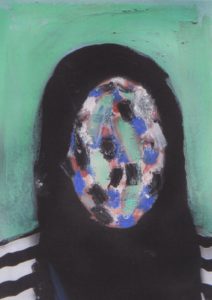

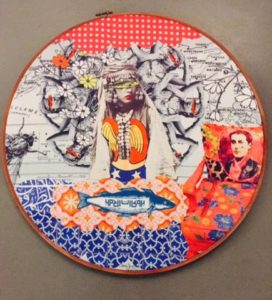

The capital city of Tripoli becomes a recurring monumental backdrop, wherein the city’s past, its signposts and architecture are intermingled with the artists’ stories and their attempt to capture and retrace the city’s disappearing and ever-changing landscape. The Ghazala installation, for example, addresses the unusual fate of the historic figurine fountain that was built by the Italian sculptor Vanetti in the 1930s and was an iconic landmark in central Tripoli for decades, before it recently vanished.

The raw history of the entirety of Libya also comes into view with reflections on its many uncomfortable episodes, including the colonial chapter, the current migrant crisis, the shifting urban landscape, the suffering under dictatorship for 42 years and the turbulent post-revolutionary period.

Looking at the known and unknown memories of Libya through the work of its citizens, both at home and abroad, the country is revealed to be a powerful force in their lives, as it is always carried in their hearts, thoughts and collective psyche and never far from their mind.

By exhibiting these artworks and hosting the parallel programme that delves deep into the Libyan artistic, cultural and intellectual terrain, it is encouraging robust discussion and reflection amongst guests and the British public.

The ‘Retracing A Disappering Landscape’ Parallel Programme

The events scheduled are below and all talks will be held at the P21 Gallery.

In Conversation: Libyan Writer Najwa Benshatwan

Date: Saturday 10 March (14:30-16:00)

Ghazi Gheblawi hosts a conversation with author Najwa Benshatwan to discuss the themes running through her highly acclaimed novel ‘The Slave Pens’. Shortlisted for the 2017 International Prize for Arabic Fiction (IPAF), the book sheds light on an ugly period of Libya’s history – when slave trade markets flourished during the Ottoman era, way before the Italian colonisation and prior to Libya’s declared independence in 1951.

In ‘The Slave Pens’ Benshatwan brings forth the narrative of the slaves in a sensitive romantic tale that touches upon the era and taboo subjects that have not been exposed before within Libyan culture. She bravely tackles the cruel trade of human beings, coming at a time when Libya has turned into a smuggler’s paradise again with African migrants being unfairly bartered.

Benshatwan is a Libyan academic, novelist and playwright, with a doctorate from La Sapienz University in Rome. The recipient of many literary prizes, she has authored three collections of short stories and three novels, including The Slave Pens. Most recently, her short story Return Ticket was featured in Banthology: Stories from Unwanted Nations published by Comma Press. She is currently at St Aidan’s College, University of Durham where she has taken up the Banipal Visiting Writer Fellowship for the duration of three months.

Gheblawi is a Libyan physician, writer, activist and blogger based in the UK. He runs and hosts the Imtidad cultural blog and podcast that focuses on literature and arts in Britain and the Arab world. He was one of the founders and cultural editor of the newspaper Libya Alyoum (2004-2009) and involved in many start-up online media and cultural projects. He is also a council member of the Society for Libyan Studies in Britain and a trustee of the Banipal Trust for Arab Literature. He is the senior editor at Darf Publishers, an independent publishing house based in London.

Khaled Mattawa: Poems Moving Pictures<>Pictures Moving Poems

Date: Saturday 31 March (14:30-16:00)

Libyan poet Khaled Mattawa presents a special talk in tandem with the overall context of the interdisciplinary show: to explore people’s direct experience of and fascination with personal memory as well as the collective narratives that arise in connection to modern day Libya.

Khaled Mattawa (born 1964 in Benghazi) is a renowned Libyan poet, highly acclaimed Arab-American writer and a leading literary translator. He is the author of four collections of poetry (Tocqueville, Amorisco, Zodiac of Echoes and Ismailia Eclipse) and two volumes of literary criticism (How Long Have You Been with Us: Essays on Poetry and Mahmoud Darwish: The Poet’s Art and His Nation).

Mattawa is also a co-editor of two Arab American literature anthologies and the translator of eleven volumes of modern Arabic poetry. His poems, essays and translations have appeared in major American literary reviews and anthologies.

Once commenting on how his poetry has been influenced by his emigration from Libya in 1979 to the United States, Mattawa said: “I think memory was very important to my work as a structure, that the tone of remembrance, or the position of remembering, is very important, was a way of speaking when I was in between deciding to stay and not stay, and I had decided to stay.”

The recipient of many literary awards, these include a Guggenheim fellowship, a USA Artists Award and a MacArthur fellowship. His work has also won the San Francisco Poetry Center Prize, the PEN American Center Poetry Translation Prize (twice), three Pushcart Prizes, final for the Pegasus Prize and a notable book recognition from the Academy of American Poets.

Mattawa is currently a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets, the premier poetry society in the United States and associate professor at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan. He is also a contributing editor for Banipal, the leading independent magazine of contemporary Arab literature translated into English.

For more: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/khaled-mattawa

Jihan Kikhia: Searching for Kikhia

Date: Thursday 19 April (18:30-20:00)

Jihan Kikhia is the writer, director and producer of the documentary film ‘Searching for Kikhia’, which is still a work in progress. Here she shares the personal journey in creating the film that is based on the true story of her family’s struggle against political and personal pressures in the search for justice, in relation to the disappearance of her late father Mansur Rashid Kikhia.

During the nineteen-year search for the missing Mansur, Baha Omary, Jihan’s Syrian-American mother, encountered some of the most powerful and dangerous people in the world (including Qaddafi himself), whilst navigating the political agendas and conflict of interests of five countries: the United States, Syria, Libya, France, and Egypt. Forced to reckon with international secret services, tortuous mystery and a clash of cultures, she still had to nurture and protect her children.

Jihan Kikhia: “Death is expected. It is closure. It is natural. Disappearance is surreal. I want to share with the audience questions such as: What is it about disappearance that makes us so confused? So disturbed? So upset? So detached yet so hooked? At times, moving on feels like you’re cheating, or that you have also betrayed justice. You somehow feel guilty that you have been unable to obtain resolution or change the situation. There is a powerlessness that is deeply uncomfortable”.

Kikhia has a Bachelor’s degree in International and Comparative Politics from the American University of Paris and a Master’s from New York University’s Gallatin School of Individualized Study, where her focus was on art education, body ornamentation and healing arts.

In 2015, her body painting project and exhibition ‘Painted Stories, Spirited Bodies’ was recognized as excellent student work in NYU’s Confluence online magazine. In 2012, her article ‘Libya, My father, and I’ was published in Kalimat Magazine: Arab Thought and Culture. She is very committed to discovering and nurturing the ways in which humanitarian aid and the healing arts merge, and how the creative process can be a vehicle for freedom and empowerment.

For more: https://www.mansurkikhia.org/

Guy Martin: The Missing

Date: Tuesday 24 April (18:30-20:00)

Photojournalist Guy Martin recalls his experience of covering political and historical events in Libya. He began to document the revolutions sweeping through the Middle East and North Africa circa January 2011and brought back images from Egypt, before focusing on the civil war in Libya from the east to the besieged western city of Misrata circa April 2011.

In this talk, he will discuss the photographs of the Libyan men that had adorned the walls of the courthouse in Benghazi during the spring and summer of 2011; because over the course of the Libyan revolution, the locals were found to be posting pictures of missing sons, fathers, uncles, cousins, brothers and friends in the hope that someone might recognise a face.

“The faces read like a ghoulish storybook of Libya’s recent history; a man who had not returned from a secret and brutal war with Chad in the 1970s; a man publicly executed in Benghazi in the 1980s; faces of men who disappeared after being arrested by Gaddafi’s secret police during his four decades of brutal rule.” Guy Martin

Martin’s work in Egypt and Libya formed the basis for joint exhibitions at the Spanish Cultural Centre in New York, HOST Gallery in London, the Third Floor Gallery in Cardiff and the SIDE Gallery in Newcastle. He also had his first solo show ‘Shifting Sands’ at the Poly Gallery in Falmouth.

His professional photographs have appeared in the Guardian, Observer, Sunday Times, The Daily Telegraph, Der Spiegel, D Magazine, FADER Magazine, Monocle Magazine, Huck Magazine, The British Journal of Photography, ARTWORLD, The New Statesman, The Wall Street Journal and Time. He is also member of the esteemed photographic agency Panos Pictures.

Originally from Cornwall, Martin studied Documentary Photography at the University of Wales, Newport and graduated with distinction. One of his first projects -Trading over the Borderline – was a documentation of the border region between Turkey and Northern Iraq and its trade routes that won him the Guardian and Observer Hodge Award for young photographers.

In 2011 Martin became an associate lecturer in Press and Editorial Photography at the University of Falmouth, United Kingdom. He now divides his time between in Istanbul and London.

For more: http://guy-martin.co.uk/

Adam Styp-Rekowski: Walks In Tripoli

Date: Saturday 28 April (14:30-16:00)

Adam Styp-Rekowski is from a legal background and has for many years worked for the United Nations and NGO’s in the Middle East and North Africa region. Originally from Poland, he is currently in Tunisia as a country director of the NGO Democracy Reporting International that looks at constitutional reforms. Prior to that, between 2012 and 2015, he worked as a constitutional dialogue project manager at the United Nations Development Programme in Libya.

Outside of these roles, Styp-Rekowski is also an expert photographer, highly respected and admired. His images are of the cities he has visited and worked in, often capturing the locals he comes across and day-to-day street scenes. Artistic both in colour and often in black and white, his ‘Walks’ portfolio covers the places and trips that have seen him enter and pass different continents.

“Camera helps to capture walks in space but also in time. I walk in places and time and share photographs of my walks…” Adam Styp-Rekowski

Styp-Rekowski’s photography has been exhibited in Jordan, Iraq, Libya, United Kingdom, Poland and Tunisia. He will be presenting images from his ‘Walks In Tripoli’ album and discuss the stories behind them.

For more: https://www.facebook.com/WalksInTripoli/

Farrah Fray: Weaving the Fabric of Our Fate

Date: Saturday 5 May (14:30-16:00)

Young Libyan writer Farrah Fray will speak about poetry, memory and contested personal history, providing a unique expository take on the idea of documenting and mapping personal and collective journeys. Informed by her background in translation and linguistics, Fray invites the audience to view Libya as a multi-modal piece of literature which, similar to the weaving of a cloth, carries routes positioned in different angles to each other and patterns repeated over the course of time, using all pieces of thread to reach a shared destination.

A published poet (The Scent of My Skin: From Libya, London and Every World I Live In), Fray’s work navigates and explores culture, feminism, displacement and identity. She is influenced by both London and Libya as well as other travels and the people she meets. Through her poems and memoirs, she hopes to expand the understanding and representation of Middle Eastern women today.

Most recently, she is working on a collaborative series with different artists for Khabar Keslan, confronting Libya’s fragmented history and identity. Khabar Keslan is an online review featuring art and critique from the Middle East, South Asia and Africa.

For more: https://www.farrahfray.com

Barbara Spadaro: Una Casa Normale

Date: Thursday 10 May (18:30-20:00)

Italian academic-historian Barbara Spadaro will deliver a talk that moves between Ottoman mansions, terrace houses and modernist flats of Tripoli, Rome and London, retracing trajectories and acts of transmission of Libyan Jewish heritage. Featuring a series of interviews and objects from family archives, Spadaro will share a strand of her research on the geographies and languages of memory of Libya.

A lecturer in Italian history at the University of Liverpool, Spadaro’s research explores media and the languages of memory in the 21st century, with a focus on Libya, Tunisia and Italy. She has been a ‘Society of Libyan Studies-British School at Rome’ fellow and visiting fellow at the Centre for the Study of Cultural Memory, Institute of Modern Languages Research, SAS University of London.

Her first monograph Una colonia Italiana: Incontri, memorie e rappresentazioni tra Italia e Libia is a study of the memories and social practices of Italian colonial families from Tripoli and Benghazi. Her most recent publication, co-edited with Katrina Yeaw, was included in the Special Issue of the Journal of North African Studies that looked into gender and transnational histories of Libya.

For more: http://translatingcultures.org.uk

Adam Benkato: Unexpected Voices (Tracing the Libyan Past in Sound)

Date: Saturday 12 May (14:30-16:00)

Libyan-American scholar and writer Adam Benkato will be exploring some very unexpected voices from the Libyan past, preserved in a recently discovered archive of vinyl LPs recorded in Libya in the 1940s. He will consider how these may contribute to Libyan memory and heritage and how they parallel the ways in which we as individuals recollect the past and the disappearing signposts.

“We view the past through images or text. Though these may be intimate and may stimulate memories, conversations, and emotions, they are also two-dimensional and are removed from the people who made them or are in them. But when we have the opportunity to hear voices, we have access to a different kind of past—one we hear directly rather than recreate for ourselves.” Adam Benkato

Benkato was raised in Houston, Texas and has lived in Benghazi and London and is now based in Berlin. His research engages with Libyan language, literature and history and addressing themes of heritage, diaspora, and post-coloniality. The curator of The Silphium Gatherer, it is a blog focused on scholarship of Libya in the arts, histories, ethnography, linguistics, literature, music, and urban studies.

For more: https://silphiumgatherer.com/

‘Retracing A Disappearing Landscape’ is generously supported and funded by the Arab Fund for Arts and Culture (AFAC), DARF Publishers, British Council and private individuals.

For more information on the P21 Gallery: http://p21.gallery/

For more information on Najlaa El-Ageli (Noon Arts Projects): https://www.noonartsprojects.com

Above Image: The Ghazala by Alla Budabbus

Note: This article was first published circa March 2018