Two years back I got a cute gift of a makeup purse made of the softest cream cotton, lined with a pretty white and red polka-dot material, with a memorable graphic design on the front. The sketched image portrayed a young female DJ wearing a Libyan style furashia with a fuming Oud incense holder in one hand, as she mixes the music on the turntable to get the invisible women to dance the night away. Reminiscent of a North African party scene, I loved it immediately and asked who made the purse. I got a name, but didn’t further investigate.

Fast forward a couple of months ago, my sister received a present delivered from Madrid, Spain that was of a babouche (North African style mule shoe) made of beautiful leather in metallic turquoise. When she tried it on, it looked good whether worn as a slipper with the heel flap down or as a shoe with the heel flap up. Again, I was intrigued by who made this and was informed it was by the same designer as the bag! Now I had to find out more of what was behind these Maghreb inspired collectables, as you would want them too! Fortunately, I got an Instagram account and made contact for a virtual interview.

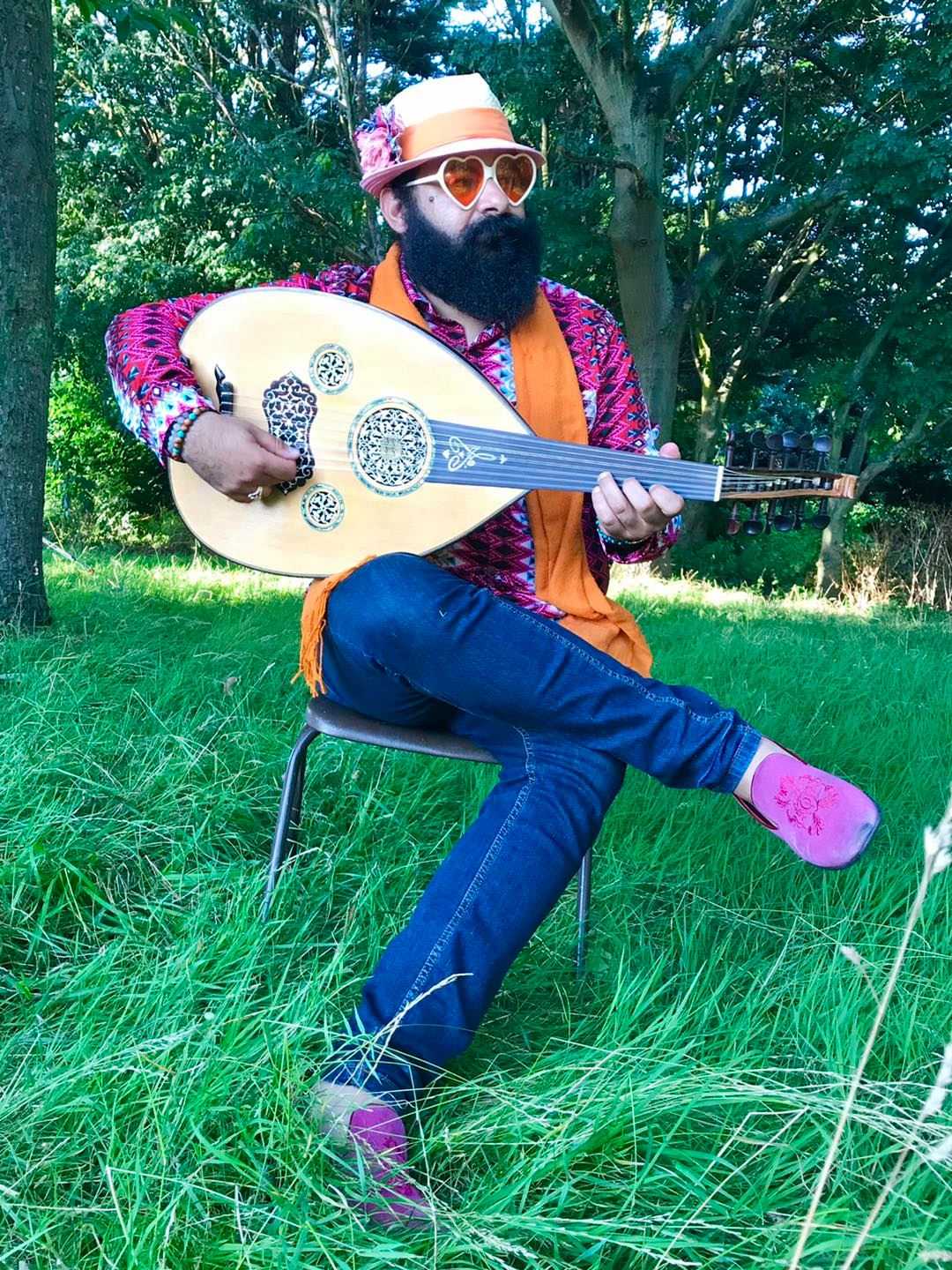

Currently in Madrid, Farah Beitelmal was born in 1985 in Tripoli, Libya. Truly a global citizen, she has lived, studied and worked in many countries throughout her life, including in: Libya, Spain, France, the United States, Egypt and Tunisia. Now married with two young children, she is a traveller with a fearless nomadic spirit, who is fluent in four languages (French, Spanish, English and Arabic) and happens to be a qualified lawyer with 15 years of experience in the legal industry, being a member of the ICC International Court of Arbitration!

The fashion business is something new and exciting for her, but it fulfils a long-held dream. Beitelmal said: “Fashion has always been an important part of my life, as I have always had an interest in fabrics, styling and creating. My mother also was always stylish and I treasure her vintage pieces. For the longest time, I was told that unless you can sew, sketch and draw, you can’t be a fashion designer and I never really challenged that.

“But, ten years ago, a friend of mine, who knew how passionate I am about fashion, took me to an event at a concept store somewhere in Madrid, where different entrepreneurs were giving a talk about their projects. Among them, there was a designer whom I approached at the end of his talk and told how much I love designing but that I could never pursue it since I can´t sketch and draw. He told me don’t’ worry if you can’t sew and draw, as long as you have the idea, you can get someone else to help you with the manifestation of it. That conversation impacted me and changed things.”

“So as often happens, it was during a crisis moment in 2013 that I thought to pursue the ambition; and, overnight, I got the idea to start with bags inspired by my Libyan homeland. I began with basic drawings with what I thought would look cool on a soft pouch. I then called my Spanish friend Jordi Machi who is a very talented painter and gave him the sketch, to say that I wanted to print it out on a bag and create a graphic design. He was happy to help until I was satisfied with a result.”

Beitmal didn’t’ just stop caring for the graphics, she also wanted the bags to be made of quality Egyptian cotton wool, be nicely lined and waterproof. In the end, she had one pouch model and another with a golden handle, using two slightly different designs. One was the Libyan furashia-clad DJ with the turntable and Oud holder, whilst the other image was inspired by old Algerian women riding scooters whilst wearing their hayek.

Beitelmal said: “These ladies are really an inspiration! They are proud of their traditions, but it doesn’t prevent them from doing other stuff. You can be anything you want to be… Libyan women especially are strong and the essence of the Farah Beitelmal brand is to show that I am a mother, wife, fashionista, Arab, European, lawyer and designer. Why do you need to put me in one box? I wish to transmit this mix of cultures and the idea that as a woman you can wear different hats, which is myself.”

But as time went by, Beitelmal got married, had her first child and took a break from her legal career and put the design ideas to the side. It was while in Tunis, where she was going back and forth between 2017-2019, that she found two concept boutiques who were happy to stock and sell the bags; and, in total, 50 of these collector items were sold out! It would be in Tunis again, a few years later that she found her next inspiration, the babouches.

She said: “I really enjoy walking around the shops and noticed these pretty slippers in a few places. I asked about the makers and was led to Chahrazed Chaieb, a Tunisian designer who works with artisans in Tunisia. I bought two for myself to try out and absolutely loved them! I then contacted her and said I wanted the babouches to be made for my brand, for which she was happy to liaise. It took some time, but we started with a standard model in 2020 during lockdown.”

Using the beautifully soft recycled Tunisian leather preferred by luxury Italian brands, Beitelmal picks up the leather and local artisans in the atelier make the babouches. Currently it is a father and son team who make them; and, as they are handmade one by one, she orders small quantities, one size per each model, unless there is a request by a client. At the moment, there are ten models with selected leathers, including: serpent leather, hair leather, soft leather and metallic. Unlike traditional babouches that tend to be hard, these are pliable, comfortable and versatile, and you can wear them two ways.

To take shape as a viable business, Beitelmal first made a few pieces and held a sample sale in Madrid, where she is based. Even without promotion on social media, she met with a positive response in the Spanish market and among her friends who are based all around the world. She also reached out to one of the Zubizarreta sisters, founders of the Zubi Spanish handbag brand, who have a unique business model, whose advice was to begin with bags, shoes and accessories before turning to clothing.

Beitelmal is insistent: “I don’t do seasons, that is important to my brand because I want to appeal to a different market. When the babouches sample sale was good, I made a collection that is both classic and timeless. The plan now is the clothing range in which I introduce season-less garments. I always choose to create something that will be with you for life and not something you buy and throw away the next day.”

“For example, the babouches can be worn to work, whether that is to a law firm or fashion magazine, or simply to drop off the kids, meet with friends for drinks or for travel. You can wear them literally anywhere and they will add spark to any outfit and make you glamorous even with your jeans and T-shirt! As I look up to well-known women in history, as well as the woman next door, I can’t define my style as such but that I am an individual who doesn’t want to be defined!”

The next big fashion move for this ever-so-resourceful Libyan woman is to launch her first ever clothing range, beginning with no more than three individual garments. She said to me: “These are chic pieces, with each telling a little more about what it means to be Farah Beitelmal!” Giving me a sneak preview, one clue is in the photo at the top of this article. In it, the designer is proudly dressed in her own creation, the ‘Lola’ coat, inspired by the legendary Spanish artist Lola Flores.

To find out more about Farah Beitelmal’s fashion brand on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/farahbeitelmal/

For the Farah Beitelmal’s sales website, from which items can be shipped to most European cities:https://farahbeitelmal.com/

Note: This article was first published on Nahla Ink circa November 2021