Living in a politically volatile city in the Middle East, a young Arab drag queen – who is by day a tireless human rights activist – is arrested by the police in the early hours of the morning for being at a cinema which is a cruising spot for working class men. He is subjected to intrusive questioning and cruel abuse by the insertion of an egg-like contraption into his rectum to test and gage his homosexuality.

Once released, though, he doesn’t make a fuss of what has happened to him. Rather, he continues with his work via an international NGO to expose local government human rights’ violations. He is also not afraid to keep performing his drag queen act at Guapa, the queer nightclub that is home to all outcasts. A brave and proud soul, he will never deny his alternative sexuality even in a hostile environment and putting his life at further risk.

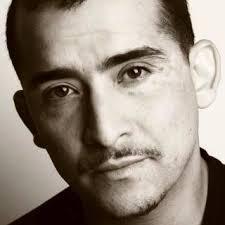

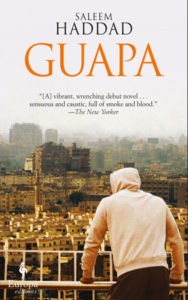

The drag queen is, of course, Maj and he is both real and not real, just like all the other characters and the events in Saleem Haddad’s debut novel ‘Guapa’. Written in the vulnerable male voice of Rasa, who confides about his gay love pain, Haddad expertly creates imaginary figures to reflect on the competing facets of Arab society, the culture and its conservative mores. It also depicts the political, economic and religious forces at war in the MENA region today.

‘Guapa’ readers will sense many a déjà vu moment as the unnamed city in the background can just as easily be Amman, Beirut, Damascus, Tunis or Cairo, that we have all either visited, lived in or seen through our computers and TV screens. This Arab city, its inhabitants and the dynamics at large are all in our collective subconscious anyway and don’t’ need to be pinned down to one place, as Haddad rightly makes this literary choice in an engaging and timely tale.

Rasa’s emotional torment and the unrequited love which threatens his reason and sanity is the main theme that enables Haddad to firstly capture our hearts – for love is love and it doesn’t’ discriminate. But as gay relations are taboo in most Middle Eastern countries, Haddad explores the not so public but private terrain from an insider perspective, as he himself is a gay Arab male who had to keep his sexuality hidden throughout his young adulthood until one day he found the courage to come out to his family and friends.

Connecting with our intellect too ‘Guapa’ features the arguments of the great known thinkers like Edward Said and Amin Maalouf on what influences the Arab identity vis-à-vis the Western world. When Rasa finds himself at a university in America in the aftermath of 9/11, he becomes the victim of ignorant prejudice and distrust by fellow students and it makes him realise that he may never be able to fully fit in there.

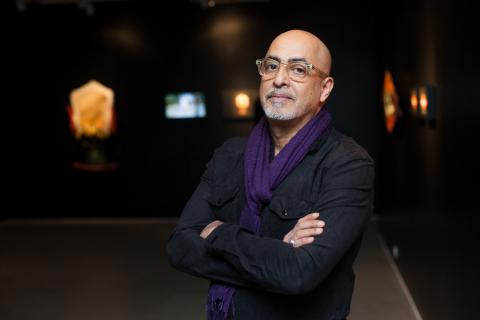

From Berlin, Haddad was kind enough to answer my questions in anticipation of taking part in the Shubbak Literature talk titled ‘A New Confidence’, where he will be joined by Alexandra Chreiteh, Amahl Khouri and Alberto Fernández Carbajal to discuss recent queer writings.

Nahla: What is it really like for the LGBT communities in the Middle East? Is there more freedom in some countries and not others or would you say it is oppressive in all of them?

Haddad: “What are we talking about when we talk about ‘freedom’? Freedom from what exactly? Freedom from community? From government? From society? And what do we lose when we free ourselves from society? That sort of freedom can be very lonely and these are the sorts of dilemmas the characters in Guapa are grappling with. And what about the concept of ‘oppression’? Oppression is multi-faceted and is not as simple as victim and perpetrator. I find it more useful to look at oppression as systems and structures that are dynamic and constantly changing.

“I also believe that the binary of ‘freedom’ and ‘oppression’ is not a useful way of looking at any situation, including that of LGBT communities in the Middle East. In any case, it’s impossible to speak on behalf of millions of LGBT individuals across the Arab world. I think it’s important to recognise the diversity of experiences and how elements like social class, geography and politics play into the experiences of LGBT communities. This is certainly something I tried to do in the book.”

Nahla: Rasa is self-loathing both when he is living in the Middle East and when he is in the West. Is this unique to his character or is it a common emotional experience for people of alternative sexualities in the Middle East due to the wide spread concept of shame and sin?

Haddad: “Rasa is a sensitive and self-aware character and in my experience sensitivity and self-awareness always bring a certain degree of self-loathing. But certainly he is battling shame, particularly around his sexuality, which he had to keep hidden from a very young age. I think gay shame is a universal phenomenon, not limited to the Arab world. I was certainly interested in exploring shame from a Middle Eastern communal context. But gay shame, sadly, remains a facet of the global LGBT community in various forms.”

Nahla: Tell me about Taymour’s character and the choice he makes to get married, deny his homosexuality and reject Rasa. Is he an archetype of something?

Haddad: “Taymour represents a certain type of fear that drives citizens to conform. It’s the same type of fear that propels Arab parents to make sure their sons study medicine or engineering and the fear that drives them to push their daughters into marrying into the ‘right’ kind of family.

“It’s the fear that drives citizens to support someone like Egypt’s President Sisi, Syria’s Bashar Al-Assad or any of the sectarian militias-cum-political-parties in Lebanon. Taymour is a representation of that sort of fear, the fear that compels people to social and political conformity. I wanted to sympathise with this conformity, I wanted to understand it, and understand why someone like Rasa might gravitate towards it.”

Nahla: The background city in Guapa experiences uprisings and a civil war situation. How were you involved in the movements circa 2011 in the Middle East?

Haddad: “I was in Beirut when the uprisings began in Tunisia and in London when the Egyptian uprising began—which is when coverage was the highest. Once the protests started in Yemen, a country I spent a lot of time working in, I tried to use my knowledge of the country to lobby British politicians and policymakers to support the uprisings. And as they progressed, I began to work with an NGO that worked with youth and women activists in Egypt, Libya and Yemen. But in many cases I found myself stuck in an odd position, as both an outsider and an insider. In many ways, it was a good position from which to write this sort of novel.”

Nahla: Do you see yourself as an LGBT activist? What are the challenges facing the LGBT rights movement in the MENA region?

Haddad: “I don’t see myself as an LGBT activist, though I recognise that having published the novel I am a voice for the community. Still, it is not a title I am comfortable with. In the end, I am a writer and if I am seen as a representative of anything, I will only disappoint. There are many brave LGBT activists and allies of the LGBT community who are working tirelessly through the region that are doing fantastic work, much more than anything I have ever done – they are too many to name.

“But I have heard from the LGBT community in the region that the novel has struck a chord with many of them, and so I’m proud for the novel to be part of a growing queer Arab culture.”

Nahla: In the novel, Rasa entertains the fantasy of escape with his lover to a Western country where he thinks their sexuality won’t be a problem. And, in your own life, you live in the UK with your partner. But what is it really like for the gay Arab person who is unable to make such an escape and is bombarded by religious and cultural forces that negate his homosexuality?

Haddad: “Is my sexuality not an issue in the UK? The only time I have been called a faggot and threatened with violence was in London, just fifteen metres from my house in Hackney. Though certainly, the situation for LGBT communities in the West is much better than in the Arab world. And from my own experience, growing up as a sensitive and slightly effeminate young boy in Kuwait and Jordan, I faced some relentless bullying and violence at the hands of other boys who sought to punish me for not fulfilling social ideals of masculinity.

“But I think we should try to avoid simplistic binaries that assume the West equals freedom and the Arab world equals violence and death. As for how to tackle homophobia in the Arab world, I would caution any sweeping statements about homophobia in the Arab world being driven purely by religion. I think homophobia in the Arab world is best understood by examining the unique cocktail of authoritarianism, ignorance, and misogyny – which affects all people in the region in different ways and to greater or lesser degrees. Thus, in tackling homophobia, I think we need to tackle all three of these elements.”

Nahla: I was very intrigued by the character of the mother who runs away from her son and husband without an explanation as to why. Can you tell me what inspired her personality and which archetype does she represent?

Haddad; “The mother character was probably the hardest character to write. I suppose because in many ways she represents a certain sensitivity and radical truth that I myself had to hide from society at a very young age. I learned the hard way that to be a man in the Arab world, one must not show sensitivity, and to be a citizen in the Arab world, one must shy away from the pursuit of truth at any cost. So in many ways, the fate of Rasa’s mother is reflective of how the characters – not just Teta, but Rasa and his father as well – chose to deal with their sensitivity and their fear of facing truth.”

Nahla: One last question. Who inspired the character of Maj?

Haddad: “Many friends inspired the character of Maj; but, fundamentally, I suppose Maj was inspired by the kind of person I aspire to be.”

——-

Note: This article was first published circa July 2017 in collaboration with the Shubbak Festival

For more information on the Shubbak Festival: http://www.shubbak.co.uk/