Using resentful rhetoric to justify his executive order made early last year – to ban the entry of people coming from seven Muslim-majority countries into the United States – President Donald Trump was indicating that America needs to be protected from these ‘other’ people on the count of their religion. A religion that is a personal faith to over 1.8 billion worldwide which he simply reduces to an enemy of ‘his’ great nation, using the language of fear and dangerously manipulating the historical context.

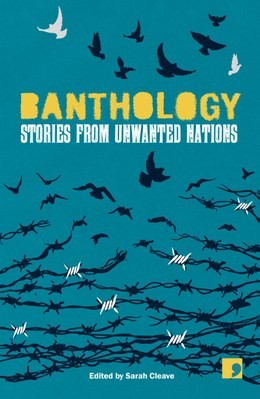

In a creative response to what can only be described as a hysterical political measure, Comma Press, the champions of the short story form, commissioned seven writers from the original countries in Executive Order 13769 – Sudan, Syria, Somalia, Iran, Libya, Iraq and Yemen – to contribute to an anthology that would be published in the UK and the US. Five of the entries were penned in the native languages and have been translated into English.

“The idea for this book was born amid the chaos of that first ban, and sought to champion, give voice to, and better understand a set of nations that the White House would like us to believe are populated entirely by terrorists. As publishers, we are acutely aware of the importance of cultural exchange between communities, and have also seen first-hand the damage caused by tightened visa controls and existing travel restrictions…” Sarah Cleave, Editor.

Opening with Rania Mamoun’s ‘Bird of Paradise’, a young Sudanese woman finds herself lost, alone and bewildered at an airport. She is psychologically frozen and unable to board the scheduled flight even though her dream had always been to run away from her oppressive life in the town of Wad Madani. Standing in the queue with the ticket ready in hand, she is held back by an emotional force and paralysed at the prospect of getting onto the plane.

Showing the mental resilience required of the refugee from a dark comic perspective, author Zaher Moareen’s ‘The Beginner’s Guide to Smuggling’ is about a Syrian man still in transit in Paris, France with a plan to get to Sweden to seek final asylum. At the mercy of smugglers who have no care as to his survival and who can never offer a guarantee of safe passage, his story reflects on what compels one to escape one’s country of origin and the myriad justifications one has to come up with to be granted entry at some borders. We sense his unease, anxiety and panic at the prospect of an uncertain future as he is beyond the point of return.

In Iranian writer Fereshteh Molaui’s ‘Phantom Limb’, we are presented with an unusual psychic connection that occurs between loved ones when they are separated and become physically thousands of miles apart. A troubled Kurdish-Iranian male refugee in Toronto, Canada experiences a pain that has no medical explanation, except that it happens to correspond directly with an injury endured by his mother back home in Iran, an amputated right leg.

Taking a swipe at Trump is Libyan writer Najwa Benshwatwan’s ‘Return Ticket’ that pokes fun at the preposterousness of what can happen at immigration controls and the pretexts offered when one is being screened purely based on their colour, sex, race, religion or nationality. She initially creates an imaginary village named Schrodinger that has the extraordinary powers to be able to move through time and space and where people are judged purely on good deeds and acts of piety.

But one very odd thing about Schrodinger is the grave of six Americans who came to it and never left: “not out of love, but because the walls of their own nation never stopped rising, day after day, until it was cut off from the world and the world cut off from it. Each attempt by an American tourist to scale the towering walls and return home proved fatal!”

The grandmother then narrates the endless humiliations she encounters as a woman traveller when once she tried to step outside the village in search of her husband and needing to visit some real and imagined places. In one instance, she is forced to take off all of her clothes because it is ‘a crime to feel embarrassed’, but in another, she is faced with the religious fundamentalists who tell her off for not wearing the hijab and threaten her with the punishment of hell.

Carrying us to an ancient time, Yemeni Wajdi al-Ahdal’s ‘The Slow Man’ begins at ‘The Year 100 According to the Babylonian Calendar’ and then moves us right up to the ‘400 Babylonians Era’. Highlighting confrontations and the war between the Egyptians and Babylonians, the tale alludes to how every great and mighty empire sooner or later comes to pass and is replaced by another. In the end, the narrator foresees the total annihilation of the human race as it devours itself for the sake of dominance, power and control.

Last but not least are Iraqi Anoud’s ‘Storyteller’ and Somali Ubah Cristina Ali Farah’s ‘Jujube’ that are similar in many ways but written in unique styles. Told by two young females, they both speak of the lived realities of war, its consequent tragedies, the incurred losses of dear ones, the clinging on to false hope and the nightmares that continue even when one is eventually outside of the conflict zone due to the irreversible damage and the invisible scarring.

Bringing to light the incredulity that was felt by many people at Trump’s original order, this powerful anthology offers, in the fictional short story format, all of the associated states of anger, upset, sadness, frustration, and even hilarity at this new added travel stigma. In terms of international borders and the movement of people, it relays the stories of those who end up paying the heaviest price when discriminatory and unfair laws are put into practice. It also, very effectively, turns upside down the President’s Islamophobia, especially as you enter the minds of the whose who have been forced to risk the migrant journey and come to appreciate the complex dynamics that are at play, wherein their religion is in no way of an aggressive nature.

Note: This article was first published circa April 2018