Nahla Ink is so happy to feature the works of Alia Derouiche Cherif for the duration of the Autumn Season 2021. It has been a privilege to get to know the artist online and see her pieces digitally. The happy timing coincides with Cherif’s latest solo show at the Musk & Amber Gallery in the capital city of Tunis under the theme of ‘Tarab’, running from 14 October to 4 November, 2021.

Born and brought up in Tunisia, the 52-year-old versatile creative has several specialties under her belt, including: a Masters in Interior Design, a Masters in Sociology of Art and Doctorate in Science Techniques in the Arts (1997) from the Technological Institute of Art, Architecture and Urbanism of Tunis (ITAAUT). As a Professor of Fashion Design, she has been teaching at a training state college in the northern suburbs of Tunis for the past twenty years. She tells me this college is just a three-minute walk from the turquoise waters of the Mediterranean Sea.

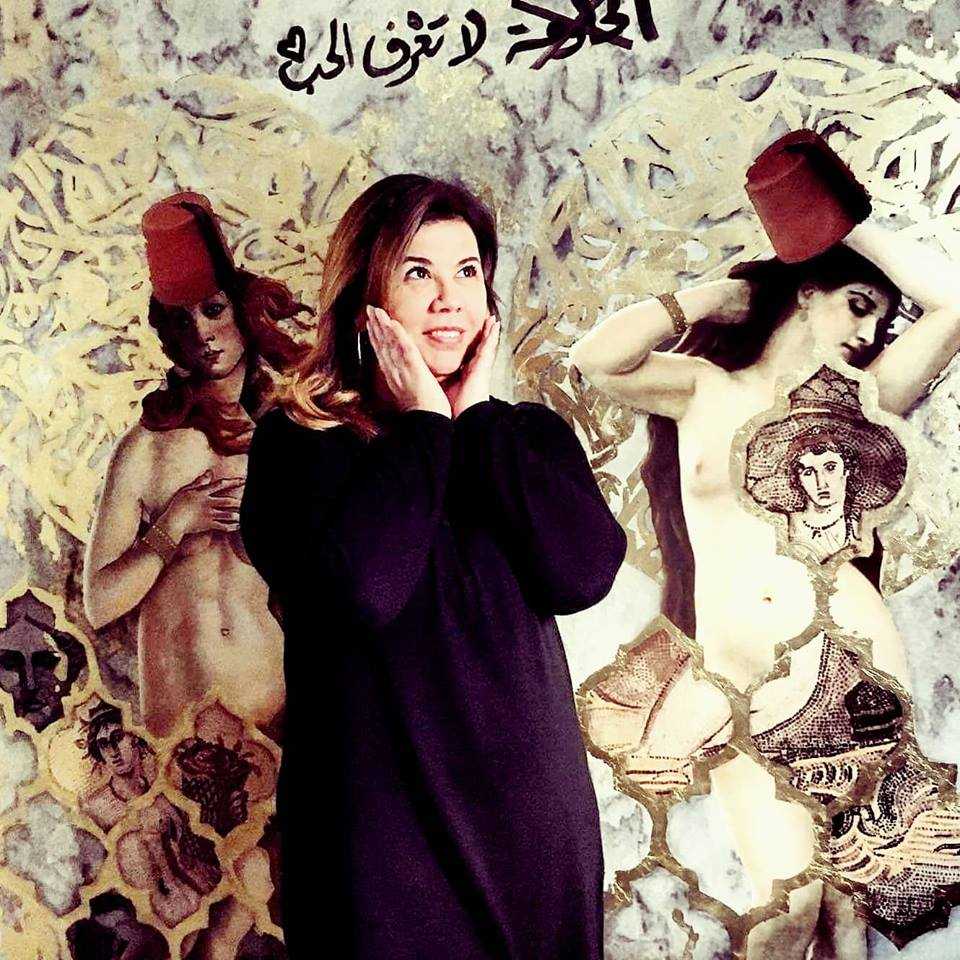

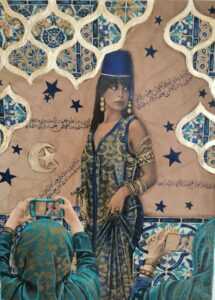

Already exhibited widely in her home country, she even caused controversy at the Bardo National Museum back in 2019 when the Minister of Culture intervened to back and support her work to the surprise of the then Director who wanted to censor it! The image above was taken of the artist at the Bardo with the artwork in question behind her. It had led to the uproar because the text on it says: “The government does not like love”!

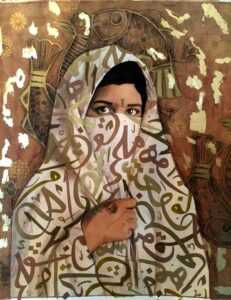

When it comes to her artwork, I was firstly drawn to Cherif’s project in relation to the depiction of Middle Eastern and North African women as found on old Colonial postcards. Originally taken by the colonisers during a certain time and age – when the art of Western photography was just blossoming and being experimented with – the shots portray the female subjects in a certain exoticized, romanticized and even fetishised way. A big question mark remains over how these individual women agreed to be pictured or how they were coerced into taking part.

So Cherif took the photographic images she found of these women and gave them a new aesthetic, a fresh interpretation and a current dimension, so that the male Orientalist gaze of the photographer is interrupted and replaced by that of an Arab woman fully in possession of her identity, gender and core human being.

There is, of course, extensive analysis regarding these Colonial photographs, the cameramen behind them and the general treatment of the indigenous populations; as well as the fact that these images are still in popular circulation today, mainly through the purchase and exchange of postcards by avid collectors and others interested in their historical value. Still for others, these images are proof of the arrogant Colonialist and his abuse, that again pertains to much academic debate and robust discussion.

About the postcards’ project, Cherif has said: “I always wanted to explore personal themes and the original idea was to do something creative with photos of my grandmother, but somehow it felt too close to heart and mind and I was blocked! So I looked for her beauty in other women as I found them in the photographs of a similar time.”

In particular, Cherif researched the works of the French-Swiss photographer Jean Geiser (1848-1923), the photos developed by the Lehnert & Landrock Studio as well as those taken by Nathan Boumendi, who were all active in North Africa, especially in Tunisia and Egypt, roughly between the late 1850s to the late 1940s.

She said: “I was led to a new reading of these Orientalist portraits and began to make my version of the old postcards, blended with my memories and with a wink to the contemporary art sphere, so far removed from the universe of these women. I wanted to give the anonymous faces, who used to be photographed without informed consent, a new life that would allow them to proudly identify and become the beloved queens and shining icons that they truly are, whom I also cover with gold. Naming these women too who have no name is to revive them!”

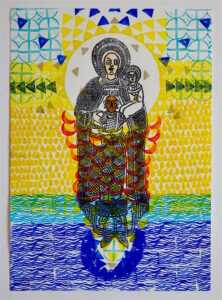

Based on photomontages printed on paper or canvas, Cherif usually employs a mixed technique with acrylics, felt pens, inks, watercolours, pencils and gold leaf for her paintings. Her dual training as an interior designer and stylist also allows her to incorporate draped zelliges, the colourful handcrafted clay tiles best known for their Moorish geometric patterns and found throughout North Africa. Added to this is use of Arabic calligraphy, that usually denotes words of love, though other times the words have no meaning, they just stand for the beauty of the letters as they flow.

Cherif’s paintings are continuously evolving and her latest project ‘Tarab’ is truly to die for, as her figures embody heady feminine power and beauty with the light, the gold and shades of blue. In this she still draws upon her personal memories and reaches out to the collective female psyche, incorporating her Arab Islamic inheritance, as well as the local North African culture with its ornaments and motifs.

She explained to Nahla Ink: “The Tarab in Arabic means an aesthetic emotion of great intensity, an ecstasy caused by a dance, or to vocal and instrumental music. I wanted to find this emotion in my paintings, with the mix of some of the old work and current references. I also want to create the sense that space and time do not exist with the zelliges, as they remain the same from centuries ago, and finally there is a nod to celebrating love itself!”

Looking forward, Cherif is scheduled to take part in two exhibitions in 2022, one in Paris, France and the other in London, UK. In Tunisia, her work has been shown at the Bardo National Museum (Tunis), Alain Nadaud Gallery (Gammarth, Tunis), the Musk & Amber Gallery (Tunis), Elbirou Gallery (Sousse) and the Efesto Salon des Artistes (La Marsa).

To follow the artist on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/aliaderouiche/

You may also be interested to read on Nahla Ink: https://www.nahlaink.com/making-the-postcard-womens-imaginarium/

Note: This article was first published on Nahla Ink circa October 2021