Nahla Ink is always that little bit extra proud to feature a Libyan artist, this time from my home city of Tripoli, Mohamed Khalifa Al Kharrubi (born in 1974), with a huge big thanks to art curator Najlaa El-Ageli, of Noon Arts Projects.

El-Ageli first presented the artist in London as part of the collective exhibition ‘Retracing a Disappearing Landscape’ at P21 Gallery, which later travelled to Spain at the Casa Arabe in both Madrid and Cordoba. The show had explored the direct experience of and fascination with memory and personal history relating to modern day Libya.

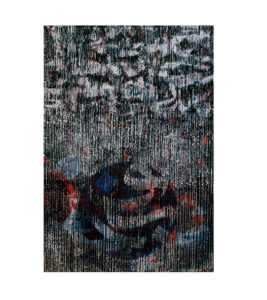

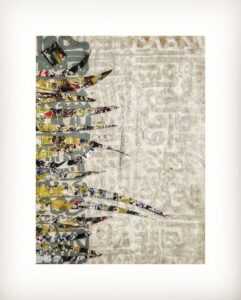

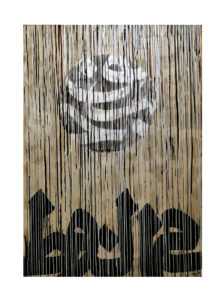

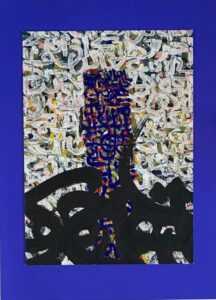

Since I have been intrigued by Al Kharrubi’s distinct style of Arabic calligraphy with the detectable Sufi undertones in his brush movement and the reinterpretation of the Arabic alphabet with the deliberately chosen words and phrases, in which we almost feel his active meditation on the meaning and the spiritual power they hold.

Having grown up and studied in Tripoli, he most recently completed a Masters of Arts at the Libyan Academy of Postgraduate Studies. His work so far has been exhibited in Libya, and outside Libya, mainly through international art fairs in Tunisia, Syria, Saudi Arabia, Austria, the UAE (Sharjah), Egypt (Cairo), Algeria, Spain, England and Italy.

I recently connected with Al Kharrubi and asked some brief questions so I could share with Nahla Ink readers a little bit more about his artistic practice. As we communicated in Arabic, below is a rough translation!

Nahla: Why Arabic calligraphy?

Al Kharrubi: I am inspired by calligraphy because it has an amazing expressive ability in the diversity of its forms, with its flexibility, sequence and overlap. It is an authentic component of my identity and affiliation.

Nahla: What words or phrases do you use and play with and why?

Al Kharrubi: Often (no) is present in my paintings, perhaps to signify the rejection of the prevailing and opposition to the familiar, but the (no) form remains what attracts me to its distinction.

Nahla: What art materials and techniques do you use?

Al Kharrubi: I tend towards an abstract style using all materials, acrylic, oil, and offset printing inks by virtue of my first specialization in the art of gravure printing (graphics). Currently I have nothing but my tools and my drawings, technically branching out to them only.

Nahla: Is Libya, as an idea, related to your work?

Al Kharrubi: Yes, but through Tripoli, it bears the fragrance of history and the present.

Nahla: Being based in Libya, what are your hopes for the future?

Al Kharrubi: To stabilize the country, so that art can flourish and keep pace with the times.

Nahla: What do you most care about in life?

Al Kharrubi: Reconciliation with oneself.

Nahla: Give me five words that matter to you.

Al Kharrubi: Freedom then freedom, justice, art and knowledge.

Nahla: Do you have a message to relay through your work?

Al Kharrubi: My message in general is that everyone finds his passion, to define his goal and strive for it with all seriousness. Art itself is a personal message. Above all I try to express myself through it. I do not seek to change the world through art because it is not an educational tool but an aesthetic value.

Nahla: Is there anything you would like to share with an international audience?

Al Kharrubi: I paint if I exist, access to the whole world has become available and easy thanks to technology. We only have to master what we do and do what we love, and the world will see us as we are.

To follow Mohamed Al Kharrubi on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/mohamedalkharrubi/

On Noon Arts Projects, highlighting Libyan art: https://www.noonartsprojects.com/