I owe my dear friend Magda a big thank you for letting me borrow her treasured copy of Mustafa Ben-Halims’s ‘Libya – The Years of Hope’, for it is not easy to come by. Although dense and heavy at 343 pages, it does add an extra dimension to the recent February 17 Libyan Revolution with Ben Halim’s heartfelt recommendations, especially for the younger Libyan generation, when he wrote the book.

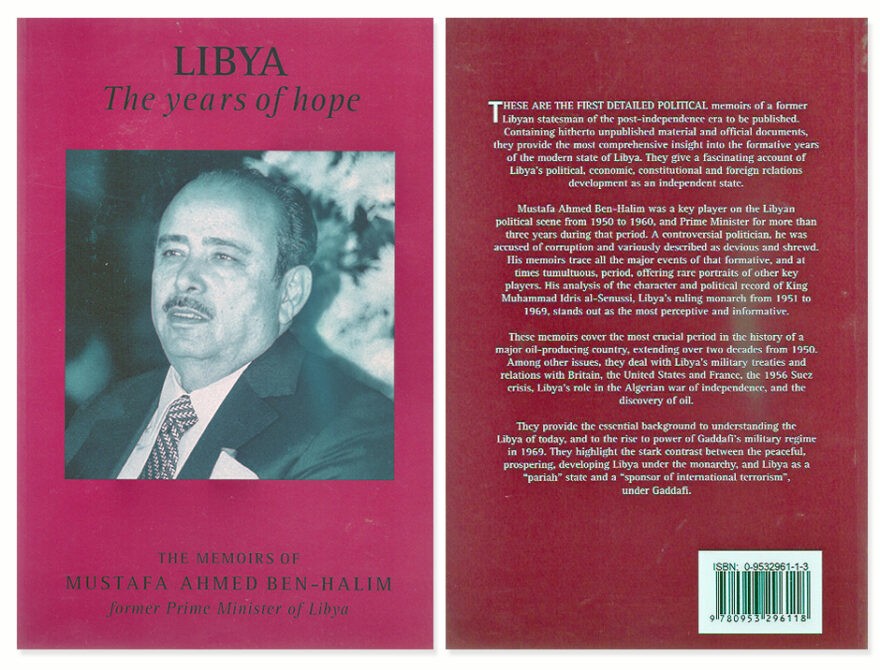

Ben-Halim, former Prime Minister of Libya during the Senussi led constitutional monarchy, published the memoirs in 1990, when he was still living in exile under diplomatic protection in the United Kingdom. Written in both Arabic and English, it documents his ten years’ worth of experience in public office and sets the record straight on the Years of Hope – as he describes them.

His goal then was to expose the Gaddafi regime’s “falsification and fabrication of history” and to fill a thirty-year vacuum of information; as well as to answer some of the severe accusations directed at him after the 1969 coup. He was brave and courageous to write this material as Gaddafi was still in power; but, considering last year’s events, Ben Halim must be very glad. He the only surviving ex-premier who witnessed the downfall of the dictatorial regime and it must for him feel like the completion of a full circle.

Not being able in 1990 to rely on important official documents for his time in office – as all were confiscated and locked up – he sets and jogs his memory on British and American official documents published after 30 years from the day of events and on newspaper archives. The former exclude other scripts which need a fifty-year-cut-off before becoming available.

Part personal biography detailing his Derna merchant family background, the childhood influences and education he received in Alexandria, Egypt and qualifying as an Engineer, the greater focus is on his time first as Minister of Public Works (1953-1954), second as Prime Minister (1953-1957), third as Private Councillor to the King (1957-1958) and last as Ambassador to France (1958-1960).

Incidentally, the memoirs offer a wonderful look at the historical dynamics some decades prior to 1951. From the day the Italians landed on the coast in October 1911, to their harsh occupation and punishing military tribunals versus the heroic local resistance movement, to the World Wars, the UN Mandate granting Libya independence, to recognition of the Senussi monarchy; and, finally, to the massive challenges faced by a virgin country that was divided, poor and in need of international political and economic support.

The entries detail the constitutional set-up, the federal institutional system imposed – and the challenges this created – as well as the big constitutional crisis faced by the Mahmoud Muntasir and Muhammad governments. We also read the specific diplomatic problems Ben-Halim had to face and the role he played in extracting and negotiating for financial aid and support from Britain and the US, in helping resolve the border problem of the French in the Fezzan, to proposing reforms to the King which never came into effect and a chapter on the story of oil.

I mostly enjoyed the part on the personality and political inclinations of King Idriss and the dangerous competitive drama that existed between his family members and the Head of the Royal Household, Ibrahim Shelhi. We also read on the assassination of the latter by the former and the awful results of that too. The King is portrayed in an affectionate way as a friend but Ben-Halim also expresses frustration with him for being too easily influenced by his entourage on matters of state and wavering at critical junctures.

There is more on the general political landscape of the Middle East in the 1950s and 1960s, the power and position of Egypt and President Jamal Nasser’s hold on popular nationalist Arab sentiments, the question of Israel and the handling of the Suez crisis. Other pages include Libya’s role in the Algerian uprising, the Tripartite Aggression against Egypt and its repercussions, the last years of the Royalist regime and finally the 1969 coup with the false promises then made.

Throughout, Ben Halim’s woes regarding that period are evident when he writes: “The nucleus of a democratic system began to appear. Many deputies performed their patriotic duty in giving direction to the government and calling it to strict account. Anyone who looks fairly at the House records will only feel a deep sadness and regret at the loss of freedom, at the strangling of that nascent democratic experiment, its destruction, repression, despotism and wrongdoing.”

Yet describing the situation a few years later: “I could see the beginnings of the deterioration of the monarchal system, and the spread of corruption which was becoming so overwhelming that it was damaging the props of constitutional rule and the integrity of public servants.”

Ben- Halim ends up paying a heavy price with the fall of the constitutional monarchy. Although he escaped imprisonment and execution by the Gaddafi regime, he was still put on trial in absentia for “corrupting political life by rigging the 1956 elections”. And, after refusing to become a Revolutionary Committee member, he was kidnapped in Beirut, Lebanon in 1973.

Had that attempt succeeded, he would have been forced back to Libya and brutally punished. Luckily, he was saved when the car had an accident and the kidnappers, hired from the Ahmed Jibril Palestinian Group, ran off. There were also several assassination attempts foiled by British Intelligence in the years that followed.

Eventually, Ben-Halim had to accept exile and so sought support and protection from his friend Prince Fahd and the King Faisal of Saudi Arabia. He describes the day when he pledged allegiance: “My raised right hand trembled. I quivered with emotion and could barely hold back the tears. I felt great pain and sadness as I gave up the nationality of my fathers for that of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, even though this is the homeland of the true Arab spirit, the refuge for free Arabs and Muslims, and the site of the Holy sanctuaries. The pain of severance I felt then I would not wish it on my worst enemy.”

Although Ben-Halim book doesn’t answer – and doesn’t claim to answer – all the questions we may have about our country’s history between independence in 1951 to September 1969, they do offer a sincere account of the years when he was Prime Minister and his own assessment and analysis of the political, social and economic forces at play.

Plus, the book should really serve as a reminder of the injustices forced upon those who chose not to sell their souls to the Gaddafi regime post-1969. Today, more than ever, it is essential to study the past in detail, so as not to repeat some mistakes and to ensure we never end up being hostage in our own country without our deserved freedoms.

Note: This article was first published circa February 2012