Why the Middle East Needs a Sexual Revolution

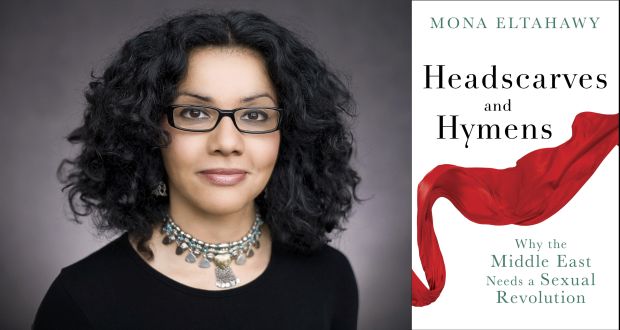

Charged with feminist arguments and emotional pleas, Egyptian author Mona Eltahawy’s debut book ‘Headscarves and Hymens’ tackles the explosive subject of what she frames as the ‘misogyny’ of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Filled with harrowing statistics on the fate of Arab women at the hands of men, the state, culture and religion, she proceeds to prescribe no less than a sexual revolution for the masses, but especially for women.

Without this, she believes that the political uprisings circa 2011 against state dictatorships cannot claim themselves to be true successes. In her self-styled manifesto, Eltahawy is calling on all Arab girls to stand up for their rights, rid themselves of the injustices that are conspiring against them and to demand fair and equal treatment to men, both in the private and the public domains.

She is also suggesting – if I have read the book properly – that they all take off their headscarves and begin the exercise of sexual autonomy outside of the culturally and religiously imposed boundaries; so that, somehow, they actively and directly claim ownership of their very own hymens. Her general advice for MENA girls: “Be immodest, rebel, disobey, and know you deserve to be free.”

Throughout the book, an insightful link is made between the public uprisings on the streets of Tunisia, Libya and Egypt – that were to topple the political tyrants – with another revolt that needs to happen against the patriarchs at home, where the fathers, husbands and brothers are guilty of mistreating the other half of the population. It also notes that the Arab women who fought alongside their male comrades within the former movements deserve their freedom also within the latter.

Sharing her terrible experience of being sexually assaulted and detained by the Egyptian state forces in November 2011, Eltahawy offers it as part of the bigger proof and evidence of the rife sexual abuses happening against women in MENA. These include the deplorable acts of virginity testing that took place against female demonstrators in Tahrir Square as well as the high incidences of rape that occurred in Libya but were never addressed nor properly punished by incoming authorities.

Sparing no Arab country however, she blames a ‘toxic mix of culture and religion’ to be working against women and a ‘triangle of misogyny’ that exists at the state, the street and the home levels. She provides plenty of disturbing statistics that have been compiled by international and local human rights organisation as well as media research, that indicate unacceptably high levels of not just street sexual harassment of women; but, also, of domestic violence and every other type of gender abuse.

Indeed it is of tremendous concern, as the book points out, that the majority of Arab countries do not offer women what should be necessary legal protection against the following practices as, when and where they occur: female genital mutilation (FGM), honour-based violence, rape, domestic violence, underage marriage as well as unfair personal laws – justified by Sharia – that disadvantage them further in the areas of inheritance, divorce and child-custody provisions.

Worse again admittedly is the societal collusion that prevents female victims from reporting crimes or challenging the stark gender inequalities. Many times led and backed by an increasingly radical religious dogma, it seems to want to take women’s rights away from them, adding to a dynamite blend that restrains their freedom. Putting a ghostly fear in their hearts and minds, they suffer in silence, for fear of bringing shame and stigma to themselves and their families, because of the concept of keeping the family or the tribal honour.

Reserving her biggest attack against Saudi Arabia, she rightly labels it ‘gender-apartheid’ led by Salafi clerics and applied by a morality police. In Saudi women still cannot drive cars nor independently get jobs without male-guardian approval. Giving the preposterous true story of how fifteen young female students were left to die in a fire, because the morality police stopped the fire fighters from rescuing them as they were not wearing their veils and abayas.

Reviewing ‘Headscarves and Hymens’ as an Arab woman, I am more than happy to support Eltahawy for tackling all of the above real and sore issues, as well as to agree the desperate need in our culture to recognise our big failings when it comes to the unfair treatment of girls and women. Certainly, we need individuals like her to open up the subject and keep up the pressure against all the societal, religious and legal systems that are being manipulated to take away women’s empowerment. This can be done by more activism and a collective responsibility to start creating the changes towards better safety, respect and equality for women; perhaps, also, by employing public engagement campaigns as well as by providing good sex and relationship education for youngsters.

Where I don’t fully agree with her is the idea that all Arab men hate women and want to suppress them. Eltahawy’s loud advice for every Arab-Muslim girl to directly challenge her family and status quo by taking off her veil and claiming sexual freedom outside of marriage is not one-hundred-per-cent convincing. If she hopes to convert them, she must be aware that each is entitled the right to choose how to experience her body and sexuality as she deems fit and also has the right to exercise her religion, should she wish to put on a veil or not.

It is very brave of Eltahawy to share with the world her intimate sexual journey and particular feminist progression, but she fails by confusing her story for that of every other Arab girl or woman. Yes, the laws need to be changed to give women freedom and protection – in both criminal and personal provisions – and all the scope to choose how to live and conduct their personal and public lives; but, to suggest, that uninhibited sexuality is the panacea for all the evils against women doesn’t exactly add up.

I do recommend reading ‘Headscarves and Hymens’ as it does deserve its hard-won flaming-hot position on the important bookshelf of Arab feminist literature. It is a sure one to get everyone fired up; and, at the very least, it will urge every woman, Arab or non-Arab, to look inwards and outwards to see whether or not there is injustice being committed against her. Whether this be at home, at work or in another environment – that can happen in any country around the world – she can at least take courage to speak up for herself and know that she has the weight of many others, like Eltahawy, behind her.

Note: This article was first published circa May 2015