Guest Review: Salma Ahmad Caller

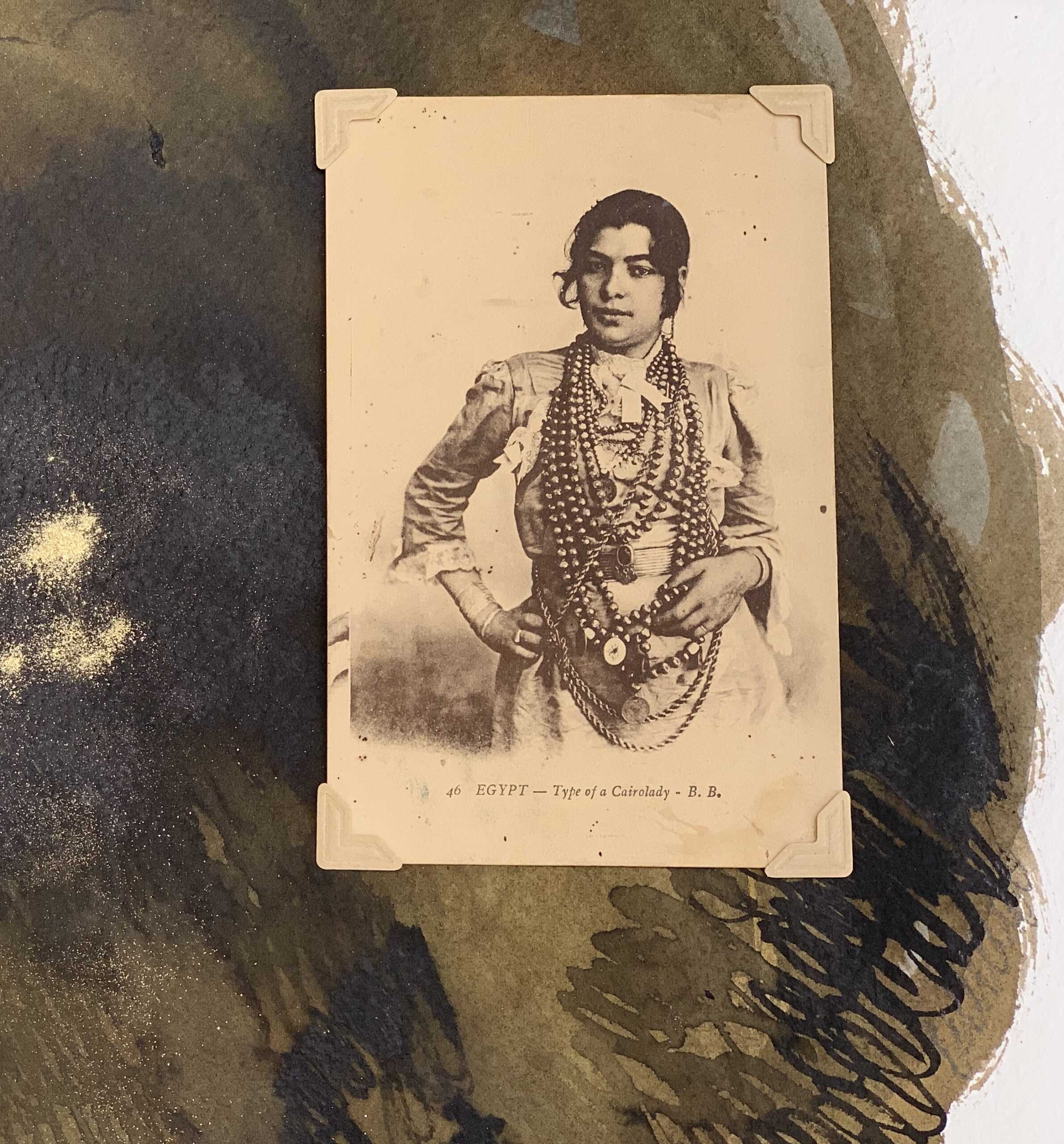

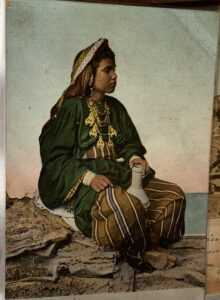

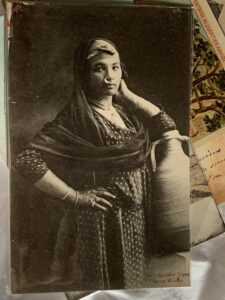

In the summer of 2018 I began a journey to explore my dual identity as an Egyptian-British woman through the investigation of old postcards of supposed Egyptian women shown through the distortions of the colonial lens. This led to an artistic project to subvert the Orientalist fantasies inherent in these images still circulating today.

I didn’t expect that Sudan would be one of the places I would most need to understand, until I began to realise that many of the postcards in my collection from Egypt feature black women or women labelled as ‘Sudanese’. My recent encounter with ‘Sudan Retold: An Art Book About the History and Future of Sudan’ gave me a profound opportunity to understand more about the complexity and beauty of Sudanese culture and history.

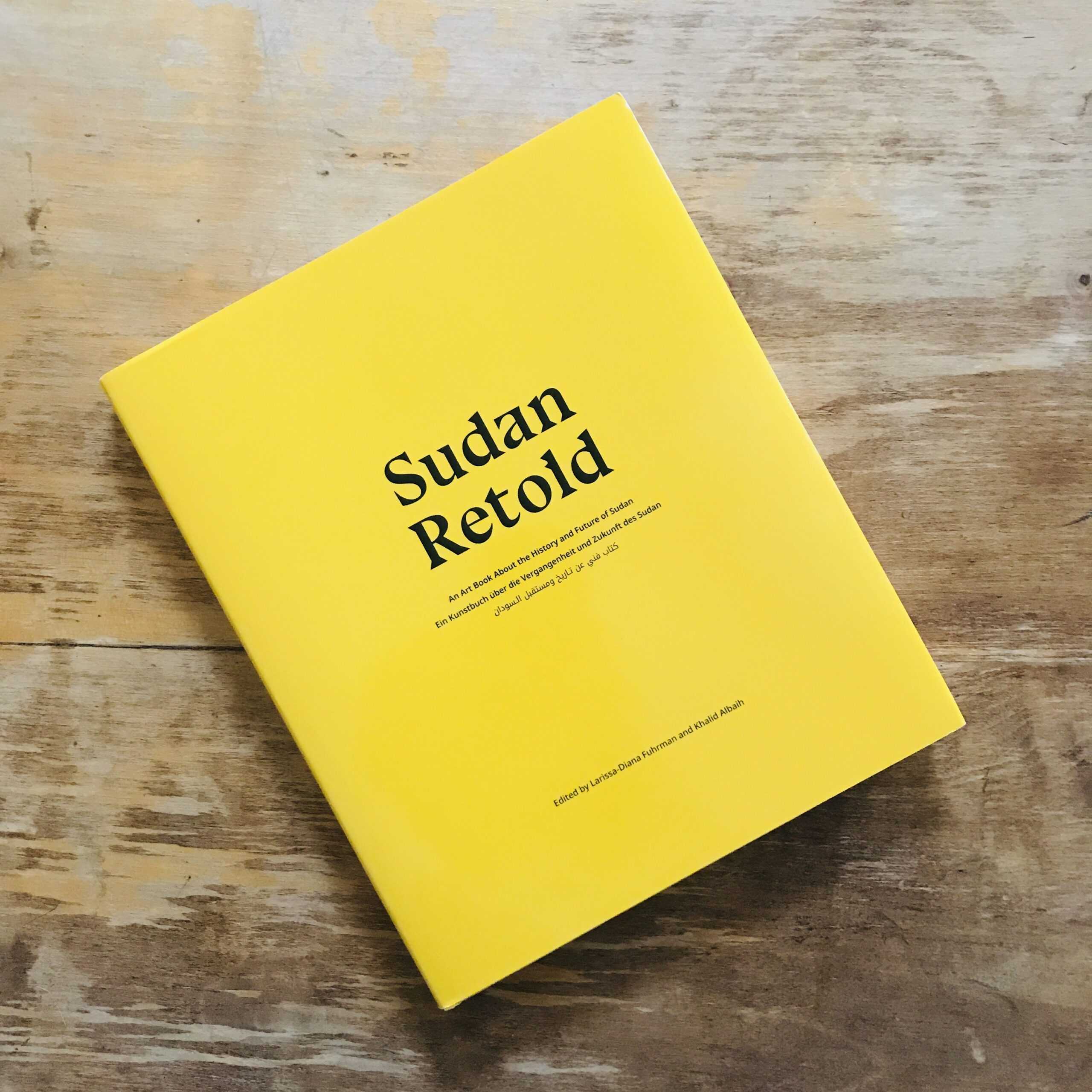

Published in three languages, Arabic, English and German, it consists of 31 chapters each contributed by different Sudanese artists, writers, illustrators, designers, photographers and a chef. It is superbly edited and put together by Larissa-Diana Fuhrmann and Khalid Wad Albaih.

From the moment I started leafing through it, I found myself walking through an archway into the past, into the ancient port city of Suakin. This mysterious experience was created whilst looking at an image by Reem Khalafallah. An imaginary ghostly soul of a slave, or a djinn imprisoned long ago by King Solomon speaks to us from the gloom of the ruins of a spectacular and fascinating past. It could easily have been the lost voices of later humans, Greek seamen, Portuguese ‘explorers’, West Africans, Venetians, Ottomans, or the English or Egyptian voices of colonising soldiers.

The ‘seen’ and the ‘unseen’ abound in her unsettling work as shadowy shapes and presences. We find ourselves looking beyond intricate mashrabiyya and dark towering walls on either side into a space inhabited by a few crows in the mist, a space of lost understanding and complex power struggles in Sudan that continue today. I say lost but not really lost, pushed into the margins of history as told by a series of colonisers and intruders.

It would seem that the djinn have been causing trouble in Suakin since at least the 15th century. This idea of creating mischief and difficulty as a tactic against intruders is an important one that appeals to me personally, and is an indirect method of resistance that women and ‘others’ often need to employ against their oppressors.

In her book ‘Civilising Women: British Crusades in Colonial Sudan’, Janice Boddy quotes a character from a colonial novel about Sudan as saying: “You are fortunate enough not to know Suakin, Miss Eustace, particularly in May. No white woman can live in that town. It has a sodden intolerable heat peculiar to itself”. One wonders if perhaps the djinn made Suakin intolerable as a form of resistance.

Boddy’s book is one of several exploring the colonial presence in Sudan and the Zar ritual that have informed my own understanding of identity in radical ways. The Zar can be considered as a women’s alternative embodied archive of memories and histories of colonisation, an archive that refuses to be pinned down or ‘civilised’ by conservatives and colonials.

The rituals of the Zar are enactments of the experience and trauma of being colonised by hierarchies of dominating intruders, and they are the ongoing negotiations with those presences as spirits within using ritual, ceremony, ecstatic dance, drumming, incense and song. They are not exorcisms but ways of accommodating violent intrusions, and a way of bringing layers of histories into living presence and creating a living archive that runs contrary to the mainstream.

Sudan Retold felt to me like the Zar, a substantial volume that brings lived experiential histories into being and into active presence. It has the effect of bringing the mischief and disruption of the djinn into any easy categorisation or labelling of Sudan.

Another significant aspect of the work in this book is that it draws upon creative imagination and mythology. The killing of ‘Chinese Gordon’ by Malaz Abdallah Osman and Mawadda Kamil is a series of silent and shockingly visceral yet detached graphic art illustrations of the stages of his death. The use of art, literature and storytelling as a form of dramatic enactment designed to recreate General Gordon as a powerful mythical Christ like figure was a colonial tool used by Imperial powers. They knew only too well the potency of imagination to retell history and control the emotions and actions of others.

Osman and Kamil take this colonial mechanism of the Gordon cult and use it for new and radical means; it is as if they were both empathising with Gordon and at the same time destroying the colonial Gordon cult that facilitated future atrocities of ‘revenge’ in Sudan by Kitchener and others.

The everyday world where facts are valued above all else fails to understand the transformative role of myths, fables and the imagination and their power to reincarnate lost histories and carry cross-generational memory into the present. The images of Suakin and the stunning work of Enas Satir and Hussam Hilali for their chapter ‘The Golden Kingdom’ (inspired by the town Berenice Panchrysos meaning Berenice the all-golden, an ancient town near the gold mines of Jebel Allaqi), are very potent metaphors for the rediscovery of erased or ignored landscapes of identity and knowledge.

The fictional worlds the artists create through image and text are living landscapes that we walk through and understand through the experience created. Satir and Hilali create a sensual legend about Berenice as an ‘African Beauty’ with dark hair and eyes the colour of gold. She lived in the dry scorching lands between today’s Sudan and Egypt, where the Black Pharaohs created their kingdom and sanctuary. It was there the Blue Djinn fell in love with her and wanted to hide her and the kingdom of gold from civilisation and its greed. So he created a mirage in the heat that hid her and the whole kingdom, thus erasing them from the history books.

This seemingly simply tale is a mythology that reveals deeper truths about colonisation and resistance, working as a disruptive mode that evades the written history books of the colonisers. What we today call Sudan is too multifarious, of many voices and bodies, to be constrained and contained by any conventional telling.

The ‘Creation Story of the Nuer’ by Malaz Sami, on morality and immorality of humans, mysteriously hints at another ‘forgotten’ mythology, of the Nuer of South Sudan, the second largest ‘ethnic’ group as Google might say in that expected semi-ethnographic disembodied and ‘fact’ telling way. But Google, of course, fails to understand that mythologies are profound and complex dwelling places for the embodied knowledge of land and place. They are not just ‘stories’.

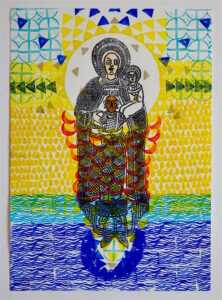

‘The City of Faras in the Christian Era’ is a poetic and mesmerising series of works by artist Dar Al Naim Mubarak that give the beautiful lost city another chance through the conduit of the imagination, her voice speaking from the future, and based on the stories of her father. We are told that a flood hid the city from the eyes of the future. This is a recurring theme, that what has been lost has actually been hidden and protected, by djinn, mirages and floods, and can be found again unsullied and alive within the people of Sudan.

The moving beauty of the everyday, often neglected and ignored, is also very much alive in Sudan Retold. In a chapter just called ‘Women’ Enas Ismail and Yasir Abuagla reveal sumptuous and moving photographs of older women from southern and western Sudan. Each woman is carrying her lived life and experience with dignity and grace, the folds and textures of clothing shimmering or falling softly around her strength and enduring determination.

Omer Eltigani, a chef from Khartoum, writes about ‘Aisha the Fadadia’. She is the breadwinner and the caretaker. Aisha makes merissa, one of the oldest beers in the world. She fights against government clampdowns on alcohol and the snubs of other women looking down on her. He brings to life the smell of the fermenting dough balls, the food she cooks for her patrons, the buzz and liveliness of her being and her resistance to conservatism.

It has been so hard to only pick a few examples as each chapter is a member of a ‘body’ and there are so many fine and important drawings and works of art here. This book is a tribute to the editors’ efforts to create something beautiful and radical that transcends so-called historical facts and empty representations. It brings into living bodily presence the multiplicity of Sudan, its past, present and future, through the voices, bodies, memories and imagination of the contributors. I will be revisiting these pages long into the future.

‘Sudan Retold: An Art Book About the History and Future of Sudan’ is published by Hirnkost Verlag, and sponsored-coordinated by the Goethe-Institut Sudan (ISBN: 978-3-945398-90-6).

Salma Ahmad Caller is a British-Egyptian artist whose practice involves creating an imagery of the narratives of body that have shaped her own body and identity across profound cultural divides. It is an investigation of the painful and contradictory mythologies surrounding the female body, processes of exoticisation, and the legacy of colonialism as a cross-generational transmission of ideas, traumas, bodies and misconceptions. Her work is informed by a Masters in Art History and Theory, having studied medicine, and teaching cross-cultural perspectives at Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford.

For more: https://www.salmaahmadcaller.com/

Read Salma Caller’s other article on Nahla Ink: https://www.nahlaink.com/making-the-postcard-womens-imaginarium/

Worse was the discovery of the exploitation, subjugation and violence behind the constructed images of the women on these postcards from the Middle East and North Africa. Posted in the millions, possibly billions, images taken in the 1800s were still circulating around Europe into the1950s or even 1970s. I now have my own large collection of Egyptian colonial postcards of women that has led me to further explore the histories of the Nubians, the Ghawazee, Hungarian Egyptians, Turkish, Sudanese, Ethiopians, Armenians and Nigerians.

Worse was the discovery of the exploitation, subjugation and violence behind the constructed images of the women on these postcards from the Middle East and North Africa. Posted in the millions, possibly billions, images taken in the 1800s were still circulating around Europe into the1950s or even 1970s. I now have my own large collection of Egyptian colonial postcards of women that has led me to further explore the histories of the Nubians, the Ghawazee, Hungarian Egyptians, Turkish, Sudanese, Ethiopians, Armenians and Nigerians. I founded ‘Making The Postcard Women’s Imaginarium’ project in August 2018 and so began Phase I of the project. I got in touch with other women artists as well as writers, poets, academics and thinkers who were all exploring identity within the context of the complex relationship between the East and West. I was keen to meet people with backgrounds that connected them to Britain and Europe and also to those places with colonial histories. I wanted it to be passionate and personal for each member.

I founded ‘Making The Postcard Women’s Imaginarium’ project in August 2018 and so began Phase I of the project. I got in touch with other women artists as well as writers, poets, academics and thinkers who were all exploring identity within the context of the complex relationship between the East and West. I was keen to meet people with backgrounds that connected them to Britain and Europe and also to those places with colonial histories. I wanted it to be passionate and personal for each member. That is why we all decided not to show the postcard women directly in our work without some kind of artistic mediation or intervention. Each woman depicted on a postcard has an amazing presence that somehow reaches out beyond the attempts to portray her in a certain way and we were each responding to that in our own way.

That is why we all decided not to show the postcard women directly in our work without some kind of artistic mediation or intervention. Each woman depicted on a postcard has an amazing presence that somehow reaches out beyond the attempts to portray her in a certain way and we were each responding to that in our own way.